American, out of Chicago. Mercury was started in 1944 by Irving Green, Berle Adams and Arthur Talmadge. According to a retrospective in 'Billboard' of the 27th of May 1972 its first records were released in 1945 in the States, under the banner of The Mercury Radio And Television Corporation, and it soon had its own pressing facilities - 'BB' of the 13th of October 1945 noted the opening of a factory in Chicago and said that, in combination with another in St. Louis, the aim was to manufacture 700,000 records per week. On the 1st of March 1947 various strands of the business were brought together and The Mercury Record Corporation was formed.

Berle Adams left in 1947 ('BB', 19th July) but Mercury continued to grow, and, as a 'BB' obituary for Irving Green was to observe, it became 'the first really strong independent to embrace all repertoire' ('BB', 15th July 2006). It had interests in Country music from early on, and it took a big step forward in the R&B field with the purchase of the Keynote catalogue in 1948. When it bought Majestic Records later that same year it established itself as 'the fifth largest company in the USA' according to the 1972 'BB' retrospective. Mercury's interests extended to Classical music: 'BB' of the 15th of November 1947 reported that it intended to start a new line in co-operation with Keynote Records, 'Keynote Classics', which would feature material licensed by Keynote from a Czechoslovakian company called Gramophone. The issues eventually led to a legal tussle with Capitol, as there was some dispute as to whether or not Gramophone was entitled to license out material sourced from German firm Telefunken, Capitol having arranged a similar licensing deal with the actual Telefunken company. The courts decided in Capitol's favour ('BB', 11th October 1952), and the decision was upheld on appeal ('BB', 23rd April 1955). By that time Mercury had established its own classical division, which was in its third year of existence. Another division, devoted to Jazz, was set up in 1954, an advertisement for its first three releases was featured in 'BB' of the 1st of May. Looking back, the 1972 'BB' retrospective claimed that the company was the first to separate out Jazz and devote a whole arm to it. In addition to Jazz, Mercury was also a force in the area of Soul and in the 'crossover' ground between the two genres.

Mercury appears to have been a go-ahead kind of concern, with an eye for new developments. In 1949 it became the second major company to enter the 33 1/3 LP market, and in May of that year it announced plans to replace shellac with a substance called 'Mercoplastic', which it had been working on for the past couple of years - in addition to being the company's president, Green was a plastics engineer, which must have helped ('BB', 7th May). As well as being forward-looking it was also highly successful in the business of selling records. September 1949 saw the company setting a new record for itself by occupying both the No.1 and No.2 positions in the Singles chart, and the 1950s were amply successful, with Mercury enjoying thirty-one million-selling singles ('BB', 27th May 1972). In 1960 another member of the founding trio, Arthur Talmadge, left - he went to United Artists ('BB', 13th June). He missed out on the formation of a new label, Smash, for Pop and other material by lesser-known artists which, the company felt, might have been lost if it had been issued among all the popular things on the main Mercury label.

There was a change of ownership in the early 1960s. Dutch electrical giant Philips had licensed the American Columbia label for the UK, but Columbia was eager to have its product out on its own label. With the prospect of losing the main source of material for its Philips label, Philips looked around to see if an American label was available for purchase. It opened negotiations with Mercury, and those negotiations were successful. A six-million-dollar deal led to Mercury being merged with the Consolidated Electronic Industries Corporation, whose controlling stockholder was the US Philips trust. The arrangement meant that material could flow in both directions, Mercury gaining British and European artists from the new parent company while Philips was able to make use of the artist roster and back catalogue of its new acquisition. The availability of masters originating with Philips in Britain eventually led to Mercury putting out records by popular artists such as The Troggs, The Walker Brothers, Manfred Mann and The Herd in the States. There were no changes in staff at the time of the takeover, and Irving Green remained president. From that time onwards Mercury's fortunes were closely tied to those of Philips / Phonogram / Polygram.

In Britain, selected Mercury records were licensed to Decca initially, and appeared on the Brunswick label. A switch to Oriole took place in 1952, and the following year, after enjoying a hit with Patti Page's 'That Doggie In The Window' b/w 'My Jealous Eyes' (Oriole, CB-1156; 3/53), Oriole gave Mercury a label of its own. Its singles were all in the then-standard 10" 78rpm format but from 1955 a number of 7" 45rpm EPs came out. In 1954 the two companies joined together to form a new firm, Oriole-Mercury, in which each took a 50% share. The intention was to promote material recorded by both of the parent companies, with Mercury supplying American recordings and having the option of releasing in America product recorded by Oriole-Mercury. As a contribution to the new firm Mercury provided additional machinery to expand Oriole's pressing plant at Aston Clinton ('BB', 15th May 1954). That same year Oriole-Mercury was responsible for introducing the Embassy label for department store Woolworths. Embassy specialized in budget-priced cover versions of hits, recorded quickly and made available in the stores as soon as possible. 'BB' of the 20th of November said that the first singles had come out the previous week and that they cost a little over half the price of standard singles, which had led to dealers being worried that the public would buy them instead of the hit versions by name artists.

The arrangement with Oriole doesn't seem to have been wholly satisfactory, as 'BB' of the 26th of November 1955 commented that although the deal had a year to run there had been rumours about Pye taking over distribution of Mercury's records. These rumours turned out to be well founded. Mercury's licensing deal was ended a year early and a long-term manufacture and distribution deal was signed with Nixa / Pye early in 1956 ('BB', 21st January). It extended to records on Mercury's Emarcy and Wing offshoots - Wing was a budget-priced label. Another move, to EMI, took place in September 1958. This proved to be longer lasting; it didn't expire until the end of 1963, by which time Mercury had been owned by Philips for a year and a half. In January 1964 Philips at last took over manufacture and distribution, and Mercury remained welded to its new owner from then on.

Unsurprisingly, given its American origin and headquarters, much of the material to be found on Mercury was American in origin. In 1968, however, Philips made an attempt to broaden its scope. 'Record Retailer' of the 24th of January reported that Mercury was being given its own division in the UK, and, under the leadership of Paddy Fleming, was to enjoy a greater measure of independence in this country. A roster of British artists was already being built up. Sadly this attempt seem to have been less than successful, and just under two years later 'RR' of the 20th of December 1969 broke the news that the UK operation was being closed down. Its various functions were being returned to Philips, and, according to the article, only American recordings would be released on Mercury in future. That proved to be not quite the case, as Rod Stewart records came out among all the American ones, but until the summer of 1974 he appears to have been the sole British artist to be regularly featured. There were solitary singles by Eddie Hardin and Medicine Head in that year, and in 1975 10 c.c. came on board. In 1976 Philips seems to have made another attempt at providing British material for release on Mercury, this time a more prolonged and more successful one.

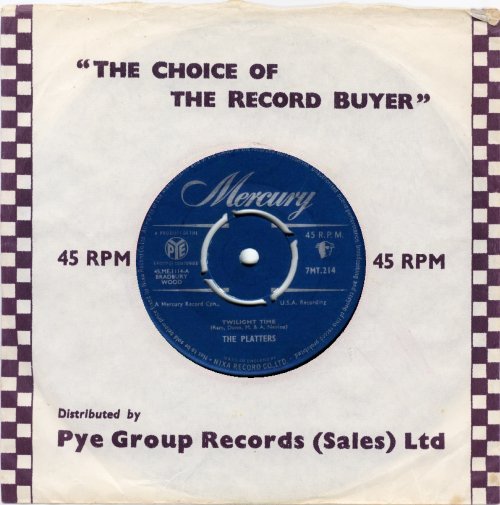

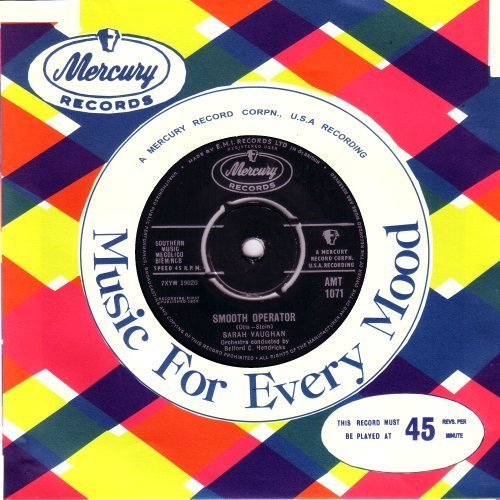

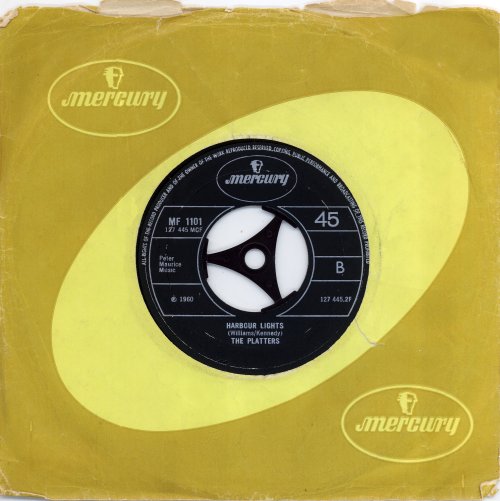

In terms of UK Singles Chart action, Mercury relied heavily on The Platters in the late 1950s. The Crew Cuts gave the label its biggest hits of 1954-55, getting to No. 12 with 'Sh-Boom' b/w 'I Spoke Too Soon' (MB-3140; 10/54) and to No.4 with 'Earth Angel' b/w 'Ko Ko Mo' (MB-3202; 4/55), while Freddie Bell & The Bell Boys also hit the No.4 spot with 'Giddy-Up-A-Ding-Dong' b/w 'I Said It And I'm Glad' (MT-122; 9/56). The Platters scored their first hits in that year, with 'The Great Pretender' b/w 'Only You' (MT-117; 9/65) and 'My Prayer' b/w 'Heaven On Earth' (MT-120; 11/56) both making the Top 5. Their next two singles were less successful but they hit a new high with 'Twilight Time' b/w 'Out Of My Mind' (7MT-214; 5/58) in 1958, which got to No.3, and finally made it to No. 1 in 1959, 'Smoke Gets In Your Eyes' b/w 'No Matter What You Are' (AMT-1019; 1/59) doing the trick. The Diamonds, Big Bopper, Billy Eckstein and Sarah Vaughan also contributed Top 20 records during that period, The Diamonds 'Faithful And True' b/w 'Little Darlin' (MT-148; 5/57) getting highest by reaching No.3.

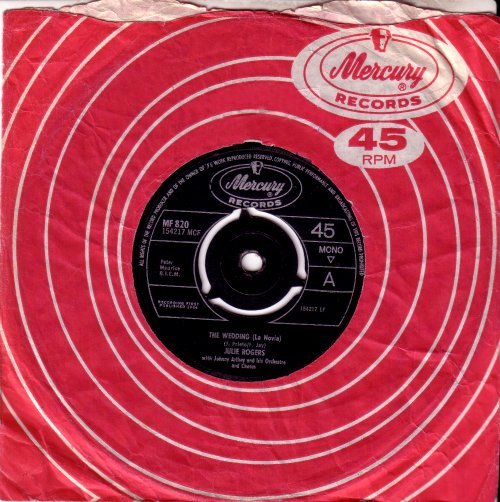

1960 saw the last of The Platters' hits, but Johnny Burnette supplied two big hits in short order, 'Running Bear' b/w 'My Heart Knows' (AMT-1079; 1/60) hitting the top spot and 'Cradle Of Love' b/w 'City Of Tears' (AMT-1092; 4/60) falling one short of that. His two subsequent singles charted but less impressively, and his final hit came in the same year as his first. Brook Benton added some lesser hits in that year and again in 1961, but Mercury's next big success came early in 1962 with Leroy Van Dyke's 'Walk On By' b/w 'My World Is Caving In' (AMT-1166; 12/61), which got to No.5. Bruce Channel provided another big hit shortly afterwards, his 'Hey! Baby' b/w 'Dream Girl' (AMT-1171, 3/62) stalling at No.2, but the label was now lacking a consistent hit-maker. Lesley Gore did well with 'It's My Party' b/w 'Danny' (AMT-1205; 5/63), which reached No.9, and Julie Rogers improved on that, hitting No.3 with 'The Wedding' b/w 'The Love Of A Boy' (MF-820; 7/64) and adding a couple of lesser successes with her follow-ups, but the only other acts to register during 1962-64 were Little Richard and The Angels, neither of whom broke into the Top 40 with their singles.

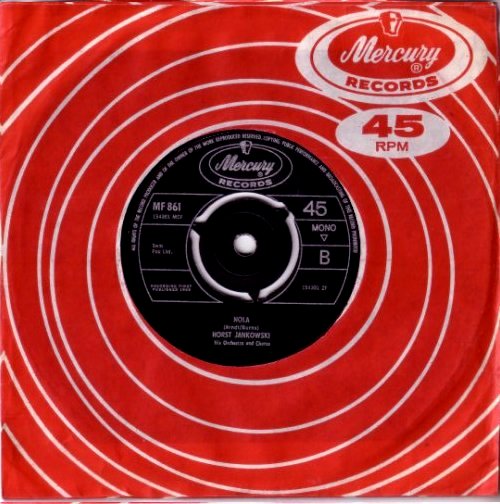

The mid- to late-Sixties were a thin period for Mercury, as far as Chart singles were concerned. Horst Jankowski's instrumental 'A Walk In The Black Forest' b/w 'Nola' (MF-861; 7/65) was a big hit, getting to the No.3 position, but it was one of only two in 1965, the other being the final entry from Julie Rogers. 1966 yielded only a No.48 from Kenny Damon, and 1967 wasn't a great improvement, with hit singles by Keith and Flatt & Scruggs not getting into the Top 20. The best that 1968 could offer was a No.19 placing for Roger Miller's 'Little Green Apples' b/w 'Our little Love' (MF-1021; 3/68) and a No.30 from Aphrodite's Child, 'Rain And Tears' b/w 'Don't Try To Catch A River' (MF-1039; 7/68). 1969 was even worse, the only Chart single being a reissue of 'Passing Strangers' b/w 'Always' by Sarah Vaughan & Billy Eckstein (MF-1082; 2/69), which had originally been a hit twelve years earlier. There were no Mercury Chart entries at all in 1970, though that year did provide two singles which eventually turned out to be of great interest: they were the first made for the company by David Bowie. 'The Prettiest Star' b/w 'Conversation Piece' (MF-1135; 3/70) and 'Memory Of A Free Festival (Parts 1 and 2)' (6052-026; 6/70) both flopped, as did a third, 'Holy, Holy' b/w 'Black Country Rock' (6052-049; 1/71), the following year. All three now command three-figure sums.

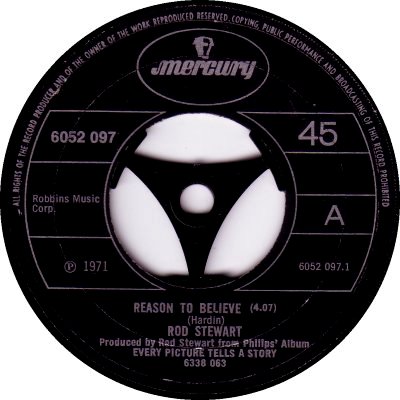

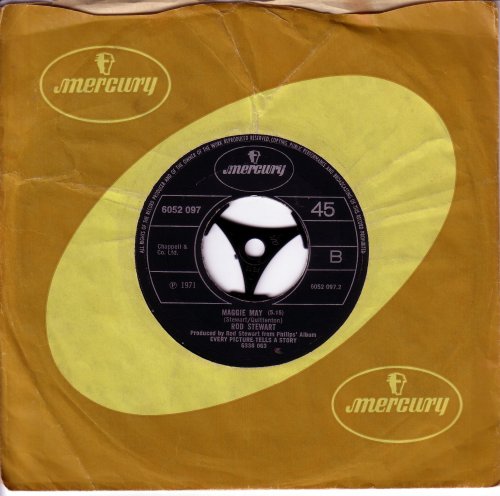

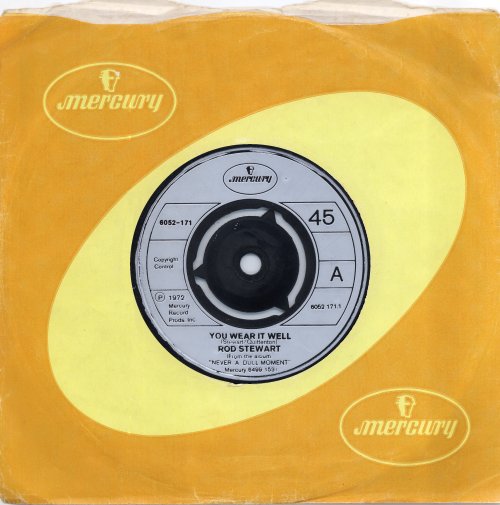

Happily for Mercury the remainder of the '70s found them getting back on track. For a start they found two artists who could be relied upon for frequent big hits, and another whose popularity was undoubted even if it was more short-lived. First came Rod Stewart, who, after switching from Phonogram's 'progressive' offshoot Vertigo, provided both of Mercury's 1971 hits and two of its three in 1972, finding the No.1 position twice in the process, first with 'Maggie May' b/w 'Reason To Believe' (6052-097; 7/71), then with its follow-up, 'You Wear It Well' b/w 'Lost Paraguayos' (6052-171; 8/72). He followed those five with three more Top Seven entries before departing for Warner Bros in 1974. Fortunately an adequate replacement was at hand. 10 c.c. joined from Jonathan King's 'UK' label in 1975 and continued the run of successes that they had enjoyed with that company. Their first single for Mercury, 'Life Is A Minestrone' b/w 'Channel Swimmer' (6008-010; 3/75) reached the No.7 spot, and their second, 'I'm Not In Love' b/w 'Good News' (6008-014; 5/75) went all the way to the top of the Charts. They went on to have five more singles in the Top Six from 1975-78, including another No.1, 'Dreadlock Holiday' b/w 'Nothing Can Move Me' (6008-035; 7/78). The third act to score highly in the '70s was the exotic American Disco band Village People. After three misses with DJM they moved to Mercury in 1978 and registered a No.1 at their first attempt, in the form of 'Y.M.C.A.' b/w 'The Women' (6007-192; 11/78). Its follow-up, 'In The Navy' b/w 'Manhattan Woman' (6007-209; 3/79) did almost as well, making No.2. The Law of Diminishing Returns set in after that, a No.15 being followed by a couple of misses, but they bounced back briefly with 'Can't Stop The Music' b/w 'I Love You To Death' (MER-16; 7/80), which climbed to a respectable No.11 in 1980.

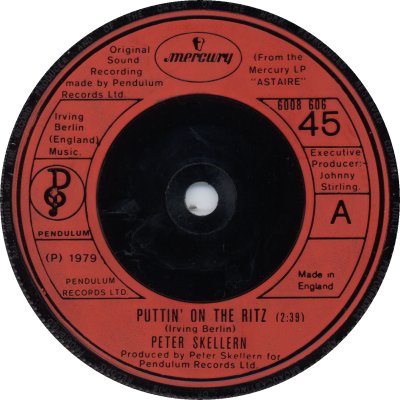

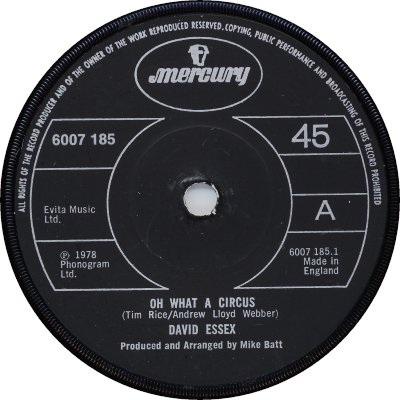

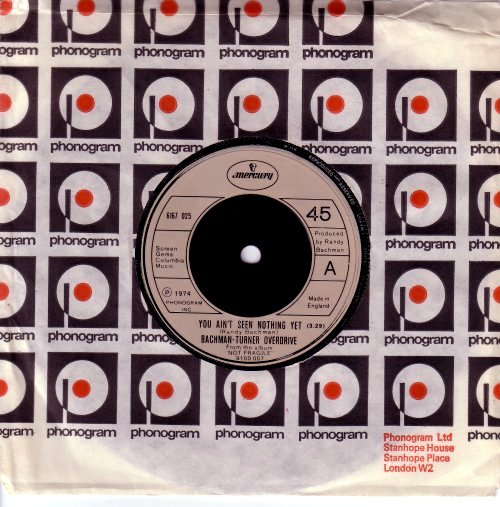

The British Punk phenomenon didn't make much impression with Mercury, though they did put out records by American punk bands The Runaways and the New York Dolls, none of which charted. They had more success with straightforward Rock. In terms of singles successes the Steve Miller Band didn't do much for them in the '70s, with just 'Rock 'n Me' b/w 'The Window' (6078-904; 10/76) making any impression on the Charts - it achieved a No.11 placing - but the band went on to much better things in the early '80s. Likewise, Rush only managed one Top 40 single in the '70s - in January 1978 - but scored heavily in the following decade. Earlier, Bachman Turner Overdrive had registered twice in 1974, 'You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet' b/w 'Free Wheelin' (6167-025; 10/74) being the more successful of the two; it climbed to second position in the Charts. Soul, Funk and Disco provided Mercury with a steady stream of Chart entries, though apart from the Village People's records they were often in relatively minor placings. Dee D. Jackson's 'Automatic Lover' b/w 'Didn't Think You'd Do It' (6007-171; 3/78) did best, reaching the No.4 spot, and James & Bobby Purify, The Bar-Kays, Hamilton Bohannon, Crown Heights Affair, the Ritchie Family and Kurtis Blow all chipped in. Additionally, in 1979 Kool & The Gang finally made their Chart breakthrough in the UK after almost a decade of trying. Their coupling of short and long versions of 'Ladies Night' (KOOL-7; 10/79) rose as high as No.9, and more successes followed in the early '80s. There were hits in other genres, too, in the second half of the decade, some from British artists as diverse as Twiggy, Lindisfarne, David Essex and Peter Skellern. As an aside, Mercury can take the credit for getting the first non-round single into the charts - initial copies of Richard Myhill's 'It Takes Two To Tango' b/w 'I Wanna Know Why' (TANGO-1; 3/78) were square, though sadly the grooves on it followed the usual circular pattern. Later copies were round, were numbered 6006-167, and were less popular. All in all, the end of the decade found Mercury in good shape. Its subsequent history is beyond the scope of this site.

The numbering of Mercury records started off simple but ended up rather complicated. As far as singles are concerned, Oriole-era 78s were numbered in an MB-3100 series; this changed to MT-100 with the move to Pye. Towards the end of Mercury's time with Pye 7" singles began to appear; the prefix of these gained a '7', becoming 7MT. The move to EMI led to the introduction of the AMT-1000 series; then when Mercury moved to Philips the AMT-1000s were replaced by the MF-800s, which eventually grew into the MF-1100s. Phonodisc introduced seven-figure numbers in 1970, that for Mercury being 6052-000. The final few MF-1100s had 6052-000 matrix numbers, but those numbers were promoted to catalogue status with 6052-016. The 6052-000s got as high as 6052-403 towards the end of 1973, with a few lower numbers coming out in early 1974, and then things started getting complicated. A 6008-000 series was introduced at the start of 1974, running alongside the 6052-000s; it seems to have covered much the same ground as the 6052s at first but was used for singles by 10 c.c. from 1975-79. Then from April to July the 6052 numbers leaped into the 6052-600s, with a solitary 6052-500 tagged on the end. In August the 6052s were replaced by a new series, 6167-000, which saw the decade out. Several other series were used alongside these. In January 1976 a 6007-000 series was introduced, which appears to have featured material originating with, or licensed by, Mercury in the UK. A 6078-800 series seems to have been used for records by the Steve Miller Band, and the 6168-800s for records from De-Lite in America. The 6160-000s appear to have been reserved for three-track maxi-singles. Singles - sometimes solitary ones, sometimes a few - also came in the following series: 6001-110, 6005-000, 6008-100, 6008-600, 6008-800, 6011-000, 6027-000, 6168-100, 6190-000, 6198-100, and 6198-200. Presumably they were sourced from various Philips companies worldwide. At the end of 1977 'Music Week' revealed that Phonodisc were to trial a return to letter / number combinations as dealers didn't care for the seven-number ones ('MW', 24th December). Mercury was affected by the change, and from the start of 1978 catalogue numbers such as 'DUSTY-1' began to appear alongside the various 6000-000s. The trial must have been successful, because from the start of 1980 Mercury's main series became an MER-0 one.

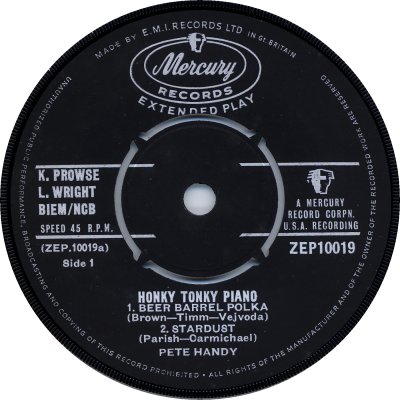

EPs had several numerical series of their own, but as they didn't last long enough as a format to be affected by the change to seven-figure numbering their system is comparatively simple. Oriole Mercurys came in the EP-1-3000 or EP-1-6000s, and Pyes in the MEP-9000s. Initially EMI had different series for Classical and Popular music and for mono and stereo recordings: ZEP-10000 for mono Pop, SEZ-19000 for stereo Pop, XEP-9000 for mono Classical and - rather daringly - SEX-1500 for stereo Classical. The final series to be used was a 10000-MCE one, which covered a spectrum from Gospel through Jazz and Country to Pop. It lasted from 1964 to 1966, after which the EP format was no longer used.

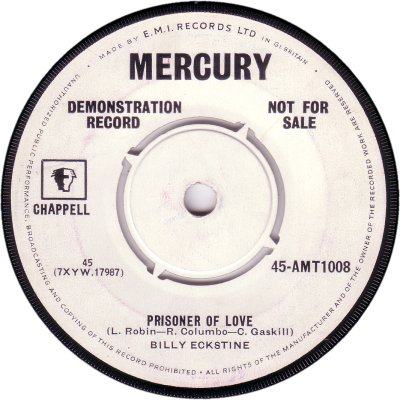

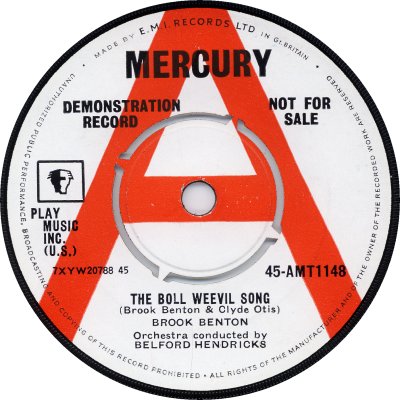

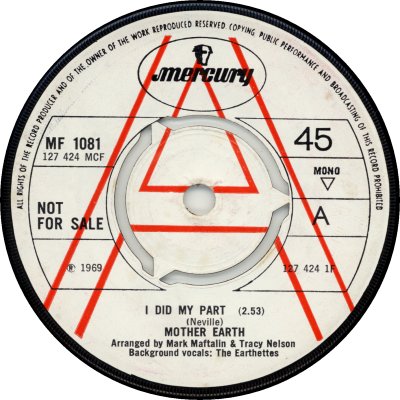

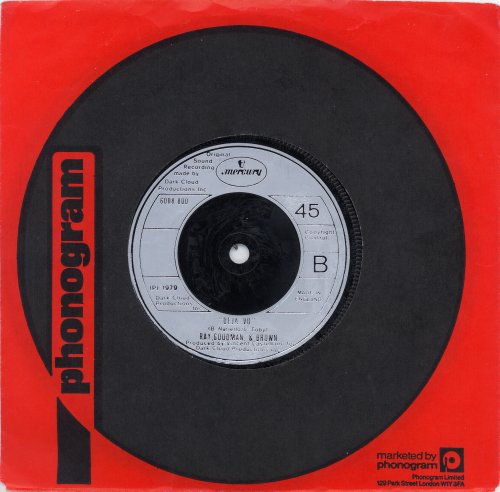

Turning to the matter of label designs, it can be seen from the scans above that there were only two basic types, but there was some variety in them. The Oriole-era EPs had black labels similar to those of the 78rpm singles, except that the 'Head' logo was smaller and the text 'Extended Play' was added (13). Likewise, during the Pye years 7" records of both types had blue labels which resembled those of the 78s, the main differences being that the 'head' moved from the top to three o'clock and the Pye logo from the bottom to 9 o'clock (1, 14). When Mercury moved to EMI the labels kept the same basic layout but the label name shrank and was enclosed in a pair of ellipses. Pop records had black labels (2, 15), while those of the 'Olympian' Classical series were crimson (16) and those of the 'Emarcy' Jazz series were mid-blue (17). When Philips took over manufacture, in January 1964, the colour and logo remained unchanged, but the Philips 'grid' appeared and there were changes in the various legends and typefaces (3). In December 1968 the logo was simplified slightly: the 'Records' was dropped, along with one of the ellipses, and the font used for the label name was simplified (5).

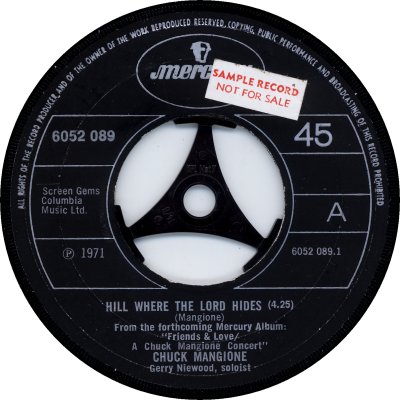

Philips-era singles in the '60s and early '70s had paper labels. Until late 1968 they were either given three-pronged 'push out' perforations (3) or, more rarely, were left intact (4). At that point some singles began to be given large spindle holes and plastic 'spider' adaptors (5); these became more and more numerous while the paper labels were still being used. In June 1973 injection moulded labels became the norm. They came in a variety of colours. Silver (6) was used for the first few singles, but it was soon replaced by fawn (7). Metallic silver-blue (8) began to make an occasional appearance at the start of 1978, and by the end of the year it had replaced the fawn. Very occasionally singles came in other colours, such as purple, green, red (9) white (10), and lime green (11). Sometimes the same single can be found in more than one colour (8, 9), or with both paper and injection moulded labels (5, 10). Paper labelled singles from later than 1973 tend to be contract pressings made by other companies. The one from 1978 (12) seems to have been made by Pye, while the EP with the white paper label (24) - a product of Phonodisc's Special Products division, made for Yardley's - looks as though it was manufactured either by EMI or RCA. That scan appears by courtesy of Robert Bowes.

With regard to demo records, the white demo (18) is an EMI pressing and dates from the 1950s; from the start of 1961 EMI demos had a solid red 'A' across them (19). Early Philips demos had 'Sample Record' on them either in the form of a sticker (20) or later a crude yellow hand-stamp, while from early 1969 to early 1971 white labels with the usual Phonodisc family 'Hollow red A on white label' design (21) were used. After these were discontinued, smaller 'Sample Record' stickers made an occasional appearance (22). In the injection moulded period pressings were made of only a few special promo singles (23).

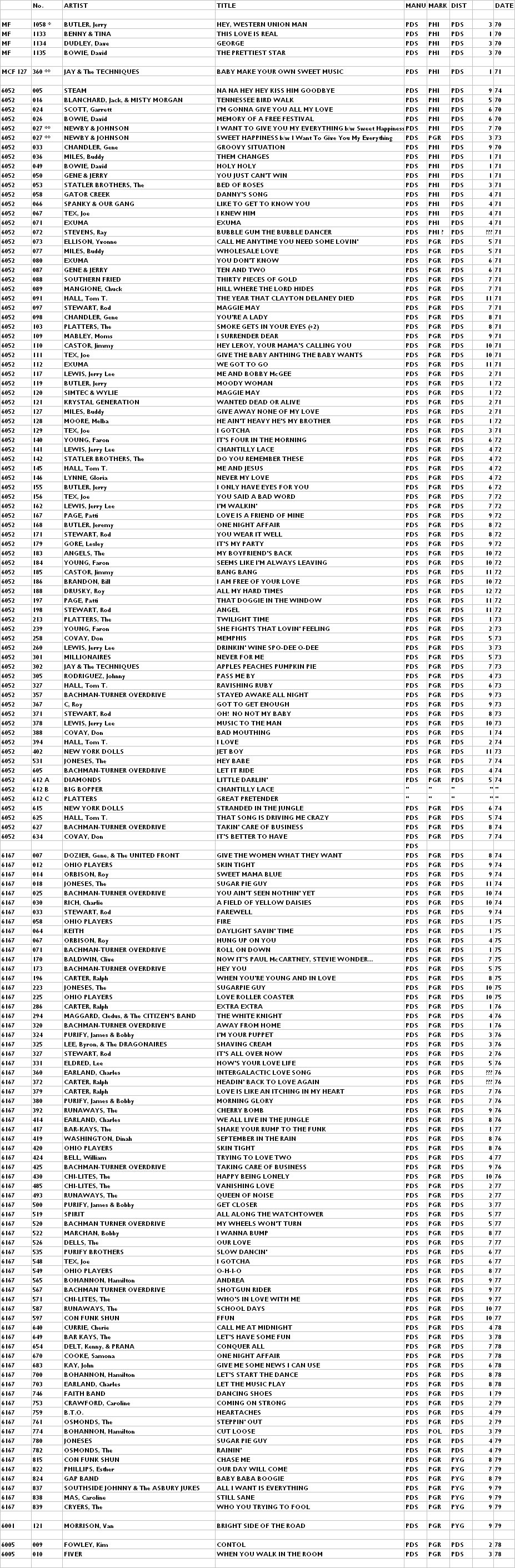

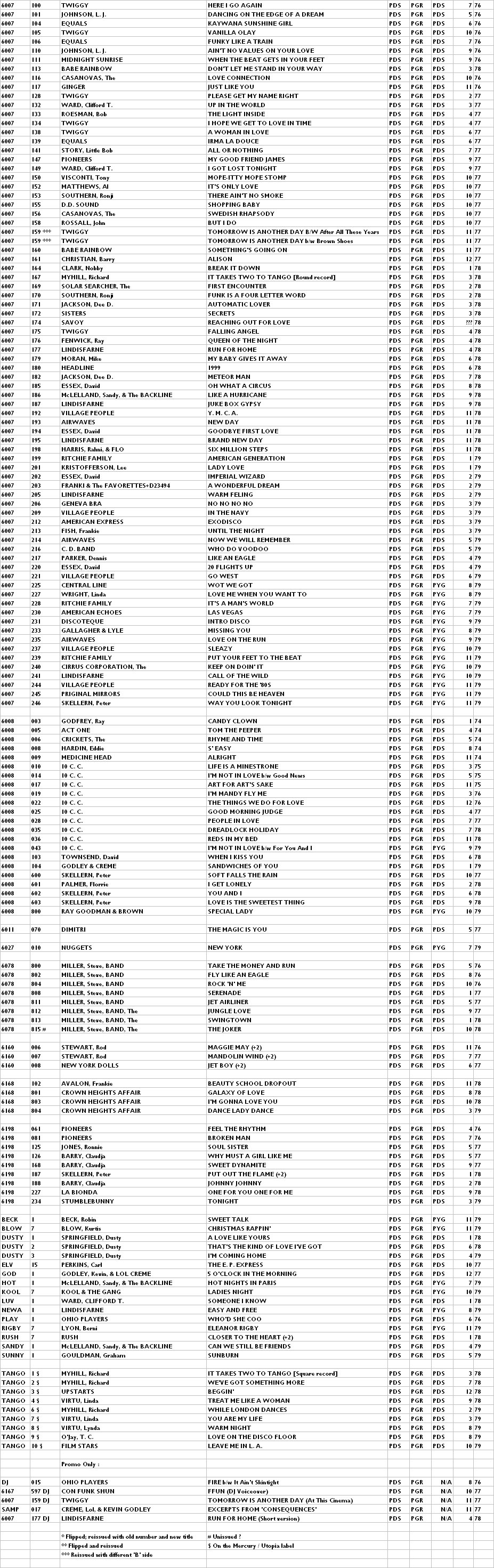

Several different company sleeves were used. Pye-era Mercurys came in the common Pye-group sleeve (25). EMI ones from the late 1950s ones were red-and-cream (26), while the tartan variety (27) dates from the early '60s. The first ones under Philips were pink and white (28), but they evolved into red-and-white (29). Initially the red-and-white sleeves were printed sideways-on; the opening on the one shown is at the right-hand side. Early '70s company sleeves featured a new design, in brown-and-yellow (30); the colours sometimes shaded towards greeny-brown-and-lemon (31) or, less commonly, orange-and-yellow (32). Along with those of the other Phonogram labels these discrete sleeves were replaced by a standard Phonogram Group one (33) in 1973; the design was changed in 1978 (34). The discography below, which has many gaps, only covers the 1970s. Most of the gaps are due to the fact that those numbers were not used for British releases. I have grouped the various blocks of numbers together, rather than attempting to put the releases into chronological order.

Copyright 2006 Robert Lyons.